In December 1926, Agatha Christie — the Queen of Crime herself — disappeared without a trace. Her car was found abandoned on a country road, the headlights still burning through the fog. For eleven days, Britain searched. When she reappeared, alive but silent, she offered no explanation. What followed was one of the strangest intersections of fame, psychology, and mystery in modern history.

The Facts

On the night of December 3, 1926, a Morris Cowley car was discovered abandoned near Newlands Corner, a remote spot in Surrey. The engine was off, but the headlights still glowed through the winter mist. Inside lay a fur coat, a driver’s license, and an expired passport belonging to Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie, then one of the most famous authors in Britain.

Christie, aged thirty-six, had published six novels by that point — including The Murder of Roger Ackroyd — and was celebrated for her logical plotting and command of human psychology. But that night, she seemed to vanish entirely.

There was no suicide note, no ransom demand, and no witnesses. The police launched what would become one of the largest manhunts in British history: more than 1,000 police officers, 15,000 civilian volunteers, and aircraft combed the countryside in freezing weather. Rivers were dragged, quarries searched, and even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, took part — bringing one of Christie’s gloves to a spiritualist medium.

As the days passed, newspapers printed daily speculation. Had the novelist been kidnapped? Was it a publicity stunt? Or — the most whispered theory of all — had her husband killed her?

The Timeline

The chronology of those eleven days has been reconstructed from police records, hotel ledgers, and eyewitness accounts. It reads less like an investigation and more like one of Christie’s own plots — except with the author as both victim and mystery.

December 3, 1926 — The Departure

That evening, Agatha left her home, Styles, in Sunningdale, Berkshire, after a heated argument with her husband, Colonel Archibald Christie, a decorated World War I pilot. Their marriage had been deteriorating for months. Agatha was still grieving her mother’s recent death, and Archie had confessed to an affair with Nancy Neele, a secretary he’d met through work at the Air Ministry.

Around 9:45 p.m., Agatha kissed her sleeping daughter Rosalind goodnight, got into her Morris Cowley, and drove into the night. She did not return.

December 4 — Discovery of the Car

At dawn, a passerby spotted the abandoned car near Newlands Corner, perched above a chalk pit. The driver’s door was open; inside were her belongings. Tire marks led to the edge of the drop, as if the car had nearly gone over. Local police concluded it was an accident or a suicide attempt — but the lack of a body complicated that theory.

December 5–8 — The Search Intensifies

The case exploded into national headlines. Police headquarters in Guildford was overwhelmed with tips. Volunteers scoured woods and ponds. The Daily Mail offered a reward for information. Reporters camped outside the Christies’ home, questioning everyone from servants to neighbors.

As the search dragged on, the public mood darkened. Rumors spread that Archie had murdered his wife to be with Nancy Neele. Others proposed that Agatha had planned the entire thing to humiliate him.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle publicly joined the effort, stating he believed psychic intuition could succeed where the police had failed. He gave one of her gloves to a clairvoyant, hoping for insight. It didn’t help.

December 9–10 — Dead Ends

Scotland Yard became involved, but despite unprecedented manpower, no trace was found. Posters and circulars were distributed nationwide. The case was now an obsession: even King George’s private secretary requested updates.

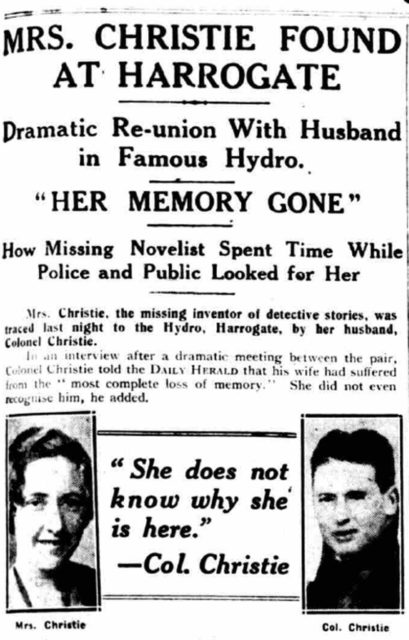

December 11 — Discovery in Harrogate

Late that evening, a musician at the Swan Hydropathic Hotel in Harrogate, Yorkshire, recognized a guest reading a newspaper article about the missing author — and realized she looked identical to the woman in the photo. She had registered under the name “Mrs. Teresa Neele of Cape Town.”

Police arrived to find Agatha alive, physically unharmed, and apparently unaware of who she was. When Archie Christie came to identify her, she allegedly greeted him with complete indifference and no recognition.

The novelist had been missing for eleven days.

She never publicly explained what happened during that time.

The Theories

Even after Christie was found, the mystery only deepened. What drove one of the sharpest minds in crime fiction to vanish in a manner worthy of her own novels? Three main theories endure.

1. Psychological Breakdown

Biographers Laura Thompson (Agatha Christie: An English Mystery, 2007) and Andrew Norman (The Disappearing Novelist, 2011) have argued that Christie suffered a dissociative fugue state — a rare psychiatric condition in which trauma or stress causes temporary amnesia and the adoption of a new identity.

In the months leading to her disappearance, Christie’s life had collapsed on multiple fronts. Her mother, Clara, had died earlier that year, plunging her into deep grief. Her marriage was failing. She was under pressure from her publisher for another book.

Norman proposed that these converging stresses triggered a psychological break, leading her to dissociate from her identity and unconsciously flee her life.

Her choice of alias — “Teresa Neele,” sharing her husband’s mistress’s surname — might not have been deliberate mockery, but rather a subconscious manifestation of the betrayal consuming her.

When police found her, doctors at the time diagnosed her with “nervous exhaustion.” Today, psychiatrists might classify it as an acute stress reaction or psychogenic fugue.

2. A Calculated Hoax

Not everyone believed the amnesia story. The Surrey police officers who led the case were unconvinced. One inspector later told the Daily Express that Christie’s behavior “suggested premeditation.”

She had withdrawn £10 before leaving home — enough for train fare to Harrogate and her stay at the hotel. Witnesses described her as calm, sociable, and entirely lucid. She played billiards, attended dances, and read the newspapers — including those about her own disappearance.

Why, then, pretend not to know who she was?

Some historians interpret the event as a carefully staged act of retaliation. By vanishing, Christie forced her unfaithful husband into the glare of public suspicion. Newspapers speculated about murder; Archie’s affair became national gossip. Within weeks of her return, he resigned from his club out of humiliation.

Whether or not Christie intended that outcome, it was exacted with the precision of one of her own storylines.

Yet this theory clashes with her lifelong aversion to publicity. Friends and colleagues described her as intensely private, even shy. The idea that she would willingly orchestrate a global scandal seems at odds with her character — unless, as some suggest, it was an act of emotional survival.

3. A Publicity Stunt

The most cynical theory — circulated mainly by tabloids — was that the disappearance was a marketing ploy to boost book sales. At the time, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd was still selling strongly, and Christie’s name was everywhere.

But evidence contradicts this idea. Christie never sought publicity and often refused interviews. Her publishers, William Collins & Sons, were reportedly furious, not delighted, by the disruption. And sales spikes after the incident were incidental, driven by the public’s curiosity rather than any planned campaign.

To those who knew her, the suggestion was absurd. Agatha Christie was, above all, a storyteller — but not at the expense of her dignity.

People and Entities

Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie (1890–1976)

Born in Torquay, Devon, Christie was raised in a genteel, upper-middle-class household and educated largely at home. During World War I, she trained as an apothecary’s assistant — a background that gave her lifelong fascination with poisons, later a hallmark of her novels.

By 1926, she was Britain’s most successful female author. Her books sold in the millions, translated worldwide. Yet despite her public success, she remained privately fragile — describing herself in letters as “permanently afraid of loneliness.”

Her disappearance reflected a collision between intellect and vulnerability: a mind capable of constructing perfect puzzles undone by personal despair.

Colonel Archibald Christie (1889–1962)

A Royal Flying Corps officer turned businessman. After the war, he and Agatha married and had one daughter, Rosalind. Their marriage appeared happy in photographs but was strained by financial issues and Archie’s emotional distance.

During the search, Archie was criticised for his aloofness. He stayed mostly in London, visiting the scene only briefly. When Agatha was found, his reaction was reportedly “more irritation than relief.” They divorced in 1928. He later married Nancy Neele.

Nancy Neele (1899–1958)

A quiet, intelligent woman who became Archie’s secretary at the Air Ministry. Little is known about her beyond her role in the triangle. To many biographers, her presence was the emotional trigger for Agatha’s breakdown. The alias “Mrs. Neele” remains one of the case’s most psychologically charged details — whether chosen consciously or not.

The Police and the Press

The Surrey Constabulary faced enormous pressure and criticism. Detectives were accused of mishandling the case and leaking information to the press. The British tabloids, meanwhile, turned the disappearance into mass spectacle. The Daily Mail, The Times, and Daily News published speculative front pages for nearly two weeks, transforming private tragedy into national theatre.

The case revealed how early 20th-century Britain consumed women’s distress as entertainment — a pattern that would repeat through later celebrity scandals.

The Evidence

The tangible evidence of Christie’s disappearance was limited but revealing.

1. The Car

The abandoned Morris Cowley showed no signs of struggle. The driver’s seat was adjusted for someone of Christie’s height; a fur coat and bag were inside. The car had stopped just before a chalk pit drop — suggesting hesitation, not recklessness. Police initially thought she had attempted suicide but changed course when no body was found nearby.

2. The Money and Luggage

Christie withdrew £10 from her bank and packed minimal luggage. These were deliberate actions — incompatible with a spur-of-the-moment flight. Her packing list included toiletries and clothes suitable for a hotel stay, not wandering or rough travel.

3. The Hotel Records

At Harrogate’s Swan Hydropathic, Christie registered as “Teresa Neele” from Cape Town. She arrived on December 4, the day after she vanished. Witnesses described her as polite, cheerful, and sociable. She joined dance nights and dined with guests.

When shown her own newspaper photograph, she reportedly commented that the missing woman looked “quite like me.”

4. Medical Examination

After her discovery, Christie was examined by doctors at Harrogate General Hospital. They diagnosed “nervous exhaustion” and “amnesia.” Her handwriting was shaky, and she struggled to recall details of her life. Yet her physical condition was sound.

Modern psychologists reviewing her case often cite symptoms consistent with dissociative fugue: temporary loss of identity triggered by trauma. It is rare, but documented.

The Aftermath

After her recovery, Agatha returned to London with her husband, but the marriage was unsalvageable. They divorced two years later.

Christie never spoke publicly about the incident — not in interviews, not in her autobiography. She omitted it entirely from her 1977 memoir An Autobiography.

In 1930, she married Sir Max Mallowan, a prominent archaeologist, and found lasting happiness. Her later travels across the Middle East inspired novels like Murder on the Orient Express and Death on the Nile.

The eleven missing days, however, continued to shadow her career. Fans, journalists, and scholars speculated endlessly. Even today, the official file remains incomplete — parts of it lost or never made public.

Analysis: What the record shows

From surviving police statements, hotel registries, and doctor’s notes, several facts emerge beyond doubt:

- She acted deliberately. Christie packed, withdrew money, and travelled under an assumed name.

- She was aware of her surroundings. Witnesses found her composed and conversational.

- She showed signs of emotional distress consistent with acute psychological trauma.

- Her memory loss was selective. She later remembered certain logistics but claimed no recollection of motive.

Modern psychiatric experts suggest that dissociative states can include partial awareness — allowing functional behavior but impaired self-recognition. In other words: she could check into a hotel and converse normally, while genuinely not remembering her former identity.

That duality — order within chaos — mirrored the very structure of her fiction.

Conclusion

By the end of 1926, the case was closed with no statement and no conclusion. The police moved on, the newspapers lost interest, and Christie returned quietly to her life.

She never spoke publicly about the disappearance, not in interviews or in her autobiography. The official explanation — exhaustion and memory loss — was accepted but never proven.

What remains are the surviving records: police files, witness accounts, and hospital notes that point to stress, preparation, and a temporary break from identity. They tell part of the story, but not all of it.

Christie went on to rebuild her career and became the most widely read novelist of the twentieth century. Yet those eleven missing days remain an unresolved entry in her biography — a gap in an otherwise carefully documented life.

Sources:

- Laura Thompson, Agatha Christie: An English Mystery (HarperCollins, 2007)

- Andrew Norman, The Disappearing Novelist (Pen & Sword, 2011)

- The Times and Daily Mail archives, December 1926

- Surrey Constabulary Records, National Archives (UK)

- BBC Radio 4, The Agatha Christie Mystery (2012 retrospective)

- Psychological analysis from British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 189 (2006): “Dissociative Amnesia and the Case of Agatha Christie”