“Every empire keeps two archives — one for the record, and one for the believers.”

For centuries, the plays of Shakespeare have been treated as scripture — cultural bedrock, literary perfection, sacred canon. But for a handful of believers, they’re something else entirely: a codebook.

Hidden in their typefaces, they say, is a message from another man — Francis Bacon — philosopher, scientist, and alleged secret son of Queen Elizabeth I.

According to them, Bacon didn’t just write Hamlet and Macbeth. He left behind a cipher, a confession, and a map.

A map that leads to a vault filled with manuscripts, inventions, and royal secrets – buried beneath stone, and silence.

The Man Behind the Mask

Francis Bacon (1561–1626) lived a double life.

By day, he was a lawyer, parliamentarian, and eventually Lord Chancellor of England. By night, he wrote about cryptography, scientific method, and knowledge as architecture — something to be built, preserved, and hidden until the world was ready to understand it.

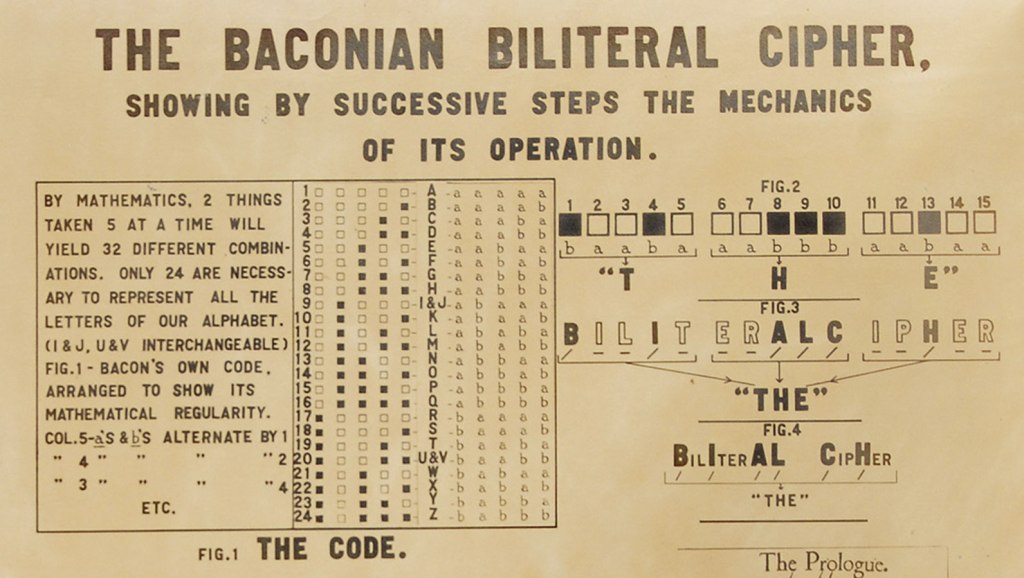

He was obsessed with ciphers. In his 1605 treatise The Advancement of Learning, Bacon outlined what he called the biliteral cipher: a way of encoding secret messages by alternating two typefaces — “A” and “B.” Each sequence of five letters represented one plaintext letter.

To anyone else, a printed page would look normal. But to the initiated, every shift in font or spacing carried meaning.

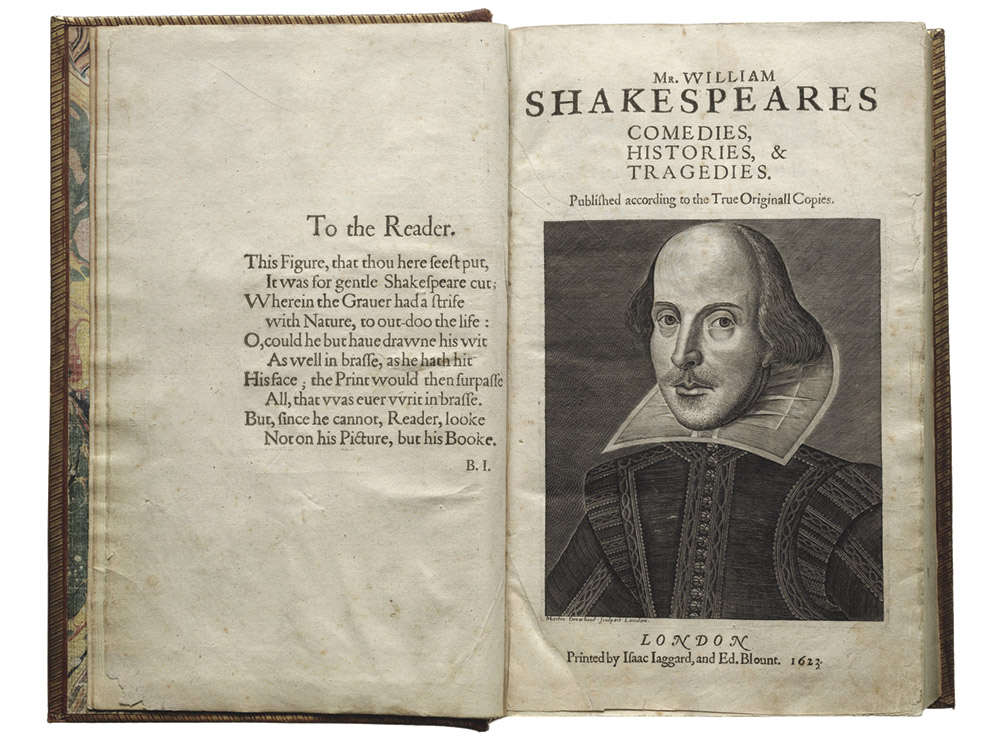

When Shakespeare’s First Folio was published in 1623 — seven years after the playwright’s death — Bacon’s followers saw an opportunity.

The Folio contained 36 plays, countless typographical inconsistencies, and, if you looked hard enough, an invitation to decode.

The Birth of a Theory

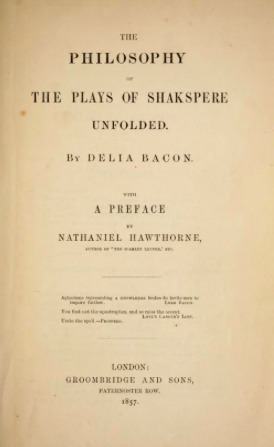

The first public challenge to Shakespeare’s authorship came from Delia Bacon, an American writer who, in 1857, published The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded.

She argued that the plays contained political ideas too radical for their time — coded messages from a group of Elizabethan philosophers led by Francis Bacon. Her hypothesis — that Shakespeare was merely a mask — was dismissed by scholars but captured the imagination of Victorian readers.

The idea metastasized. By the 1880s, it had evolved into a full-scale authorship movement, attracting cryptographers, spiritualists, and even archaeologists convinced that Bacon had left behind a secret vault containing proof of his authorship and lineage.

That vault, they said, was not a metaphor. It was a physical chamber — a time capsule of hidden knowledge.

The Doctor Who Built a Cipher Machine

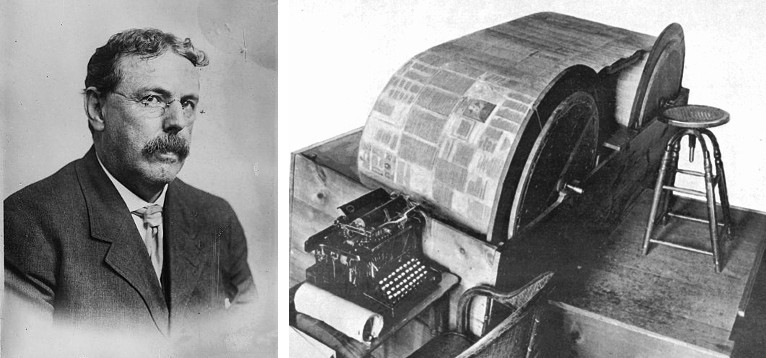

Two centuries later, an American doctor named Orville Ward Owen took that invitation literally.

In 1880s Detroit, Owen constructed what he called the “cipher wheel” — a twenty-foot cylinder wrapped in linen strips printed with the complete works of Shakespeare, Spenser, and Bacon. By spinning the wheel, he could align words and phrases, searching for hidden patterns.

After years of decoding, he announced his discovery: Bacon had written Shakespeare’s plays, confessed his royal parentage, and buried evidence of it all near the River Wye in Wales.

Owen claimed that beneath Chepstow Castle lay a vault containing gold, manuscripts, and the true story of England’s monarchy.

He wasn’t alone in believing it. Victorian audiences, living in an age of spiritualism and secret societies, were captivated. Newspapers called him “the modern alchemist.” Investors backed him.

Then he started digging.

For a decade, Owen excavated tunnels and riverbanks, claiming to find sealed chambers and “architectural alignments” matching Bacon’s cipher diagrams.

He produced no treasure. But his conviction never wavered.

When his funding ran out, he insisted that government agents had interfered — sealing the vault before he could open it.

The American Woman Who Read Between the Letters

While Owen dug, Elizabeth Wells Gallup, a Michigan schoolteacher turned codebreaker, took a different approach.

Gallup spent decades examining facsimiles of the First Folio with magnifying lenses, comparing fonts line by line. Using Bacon’s biliteral cipher, she claimed to uncover long encoded messages.

They were astonishing.

Her deciphered text, she said, revealed that Bacon was the son of Queen Elizabeth and her favorite courtier, Robert Dudley. He was the true heir to the throne, hidden behind pseudonyms and political caution.

She published her results in The Biliteral Cipher of Sir Francis Bacon (1899) and The Tragedy of Francis Bacon, Prince of England (1902).

Her claims were met with ridicule — but not silence. To many, the idea of a hidden prince turned author felt too poetic to dismiss.

Gallup’s health declined, her patrons withdrew support, and she died nearly destitute. But her work lived on — inspiring generations of amateur cryptographers convinced that literature itself could be a vault.

The Vault, the Code, and the Faith

By the early 20th century, Bacon’s supposed cipher had evolved into a global treasure hunt.

Chepstow Castle was joined by Glastonbury, St. Michael’s churches, and eventually Oak Island, Nova Scotia — each said to hide fragments of the same archive.

The logic was elastic, but consistent: Bacon had encoded the map to a secret chamber where England’s lost knowledge waited for rediscovery.

To believers, the locations formed a network of Masonic geometry. To skeptics, it was pareidolia — the human tendency to find patterns in chaos.

The truth probably sits somewhere between fascination and delusion.

Bacon did write about ciphers. He did design a method of hiding messages in typography. He did believe in a “brotherhood of learning” that preserved wisdom through secrecy.

What he likely didn’t do was bury treasure beneath Welsh castles.

Freemasons, Rosicrucians, and the Utopian Map

The Baconian story wouldn’t be complete without the Freemasons — and this is where it slips from history into mysticism.

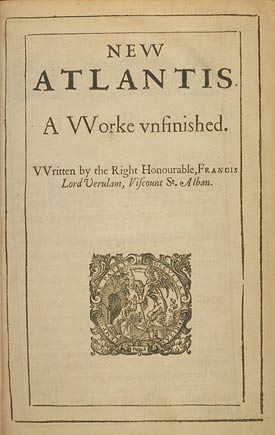

In Bacon’s final work, The New Atlantis, he described an island ruled by scholars in an institution called Salomon’s House — a place devoted to collecting, preserving, and perfecting knowledge.

Freemasons saw themselves reflected in that vision. Their symbolism — compasses, pillars, light from darkness — echoed Bacon’s metaphors of architecture and illumination.

Some Masonic historians even called him a “philosophical founder.” Others went further, linking him to Rosicrucian manifestos that spoke of hidden brotherhoods and secret vaults.

Later theorists tied Bacon’s supposed vault to biblical relics — even the lost Menorah of Solomon’s Temple.

At that point, the story had grown far beyond literature. It was about myth itself — how humans turn knowledge into legend, and legend into faith.

Scholars and Skeptics

In 1957, the American cryptologists William and Elizebeth Friedman published The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined.

Their conclusion was clear: the Baconian cipher didn’t exist.

They found no reproducible code in the First Folio — only the printing inconsistencies of 17th-century typesetters. Fonts changed at random; compositors substituted characters to fit justified lines; no consistent pattern held across copies.

Gallup’s results, they said, were unintentional artifacts — the byproduct of human bias and Victorian printing plates.

Ironically, the Friedmans’ meticulous approach helped lay the foundation for modern cryptanalysis. The same methods they used to disprove Bacon’s cipher later guided their work breaking wartime codes.

The myth had been disproven — but it had also helped invent the tools of real-world codebreaking.

Timeline:

1561 — Francis Bacon born in London.

1605 — The Advancement of Learning introduces the biliteral cipher.

1623 — Shakespeare’s First Folio published.

1857 — Delia Bacon publishes the first Baconian authorship theory.

1888 — Ignatius Donnelly’s The Great Cryptogram links cipher to Shakespeare.

1891 — Dr. Orville Ward Owen begins the Chepstow excavation.

1899–1902 — Elizabeth Gallup decodes the First Folio, claims royal lineage.

1957 — The Friedmans publish their definitive cryptologic refutation.

Present Day — The Baconian vault remains undiscovered — in fact or in faith.

Today, no credible scholar supports the Baconian authorship theory. The First Folio is understood as a product of collaborative Elizabethan publishing, not cryptographic design.

Modern forensic typographers and digital analysts — including teams at the Folger Shakespeare Library and Oxford’s Bodleian — have scanned high-resolution copies of multiple Folios and found no consistent binary pattern, no reproducible cipher, no hidden message.

Variations once considered “clues” have been traced to normal typesetting errors or compositorial drift.

And yet, new believers emerge each decade.

Some reinterpret Bacon as the proto-architect of Freemasonry; others as the father of cryptography itself. Online communities now map alleged cipher trails onto digital scans, citing “geometric correspondences” between letter spacing and Renaissance architecture.

No discoveries have held up under peer review. But that’s almost beside the point.

The Shakespeare Code has outlived its evidence because it speaks to something older than proof: the human instinct to believe that genius hides itself.